I am doing a genetics project, and whilst I have come to understand the ‘fundamental’ processes which underlie molecular biology, there are many people out there that don’t. This post thus serves the purpose of teaching those of you who interested, just a little bit about what I do and how I do it. I don’t claim to be an expert nor do I claim to be good at it, but bear with me, and maybe you will come to appreciate just how simple this stuff can be.

My project is using the DNA from spotted skaapsteker (Psammophylax rhombeatus rhombeatus) tail clippings to determine whether the snakes on the east coast, and the snakes on the west coast of South Africa, are different species. I will admit, Genetics is not exactly the most accessible science, but when you peel away the prestige created by ‘full-of-them-self’ scientists and shed your own self-doubt, you will begin to find the methods can be rather simple, and better yet, fun.

Firstly the tissue has to be acquired and this can be done in one of two ways. Either you sub-sample a specimen in a museum (ie: cut a piece of tissue off a preserved animal) or you capture the animal yourself and cut off a piece of tissue. Due to time constraints, I did not capture my own specimens but rather opted to sub-sample museum specimens from the Bayworld museum in the Eastern Cape and SANBI in the Western Cape. Once you have your sub-samples, you have to log the numbers and further sub-sample your original sub-sample. This is done to ensure that there is back-up tissue, in the event that you lose, or contaminate the sub-sample that you are working with. (FYI: I will use the word ‘sub-sample’ more sparingly from here on out)

Figure 1: To left-Test tubes, containing DNA samples from spotted skaapstekers across the southern Cape. To Right- A skaapsteker tail being sub-sampled.

Following this, the original sample is returned to the freezer, to preserve the integrity of the DNA for future use, and the sub-sample is extracted. Extraction is the process whereby the the DNA is purified and isolated from all other compounds that may be present in the piece of tissue. This is an integral step, because the more pure the DNA, the more likely it will be translated into a usable DNA sequence at the end of the entire process.Firstly the DNA sample is broken up to expose the DNA, then the fats and proteins inherent in the tissue are broken-up, using salt and detergents and finally, the DNA is separated from the solution using alcohol and centrifugation. Basically, The DNA is isolated and purified.

Figure 2: To left- process of adding and removing alcohol in the seperation step of extraction. To Right- Centrifuge used for separating DNA from alcohol

Once extracted, a micro-liter of the DNA solution is removed from the test tube and analysed using a Nano-drop to determine the concentration of the DNA in each test tube. This is done to ensure that the DNA was properly extracted and in addition, enables you to modify the ratio of water and DNA going into the PCR step to optimize the reaction. Once all samples have been nano dropped, the DNA from each test tube is transferred into new tubes and primer, mastermix and water are added to the test tube.

The purpose of a Polymerase Chain Reaction is to amplify the DNA already present in the test tubes and create higher quantities, and longer strands of DNA, that can be analysed in the last step of the process. The primer which is specific, amplifies a particular gene and the mastermix supplies the building blacks, facilitates the binding process and ensures the right conditions are met for DNA amplification.

In my project, I am analyzing the 16s RNA gene so naturally I used a 16s primer to amplify the gene I was looking for. The entire process takes place inside a PCR machine which cycles the temperatures for specific periods of time in order to facilitate the amplification process inside the test tubes.

Figure 3: To left- Nano-drop, used to test the DNA concentration of samples after extraction step. To right- PCR machine, cycles temperature thereby facilitating the amplification of DNA.

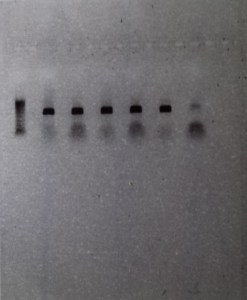

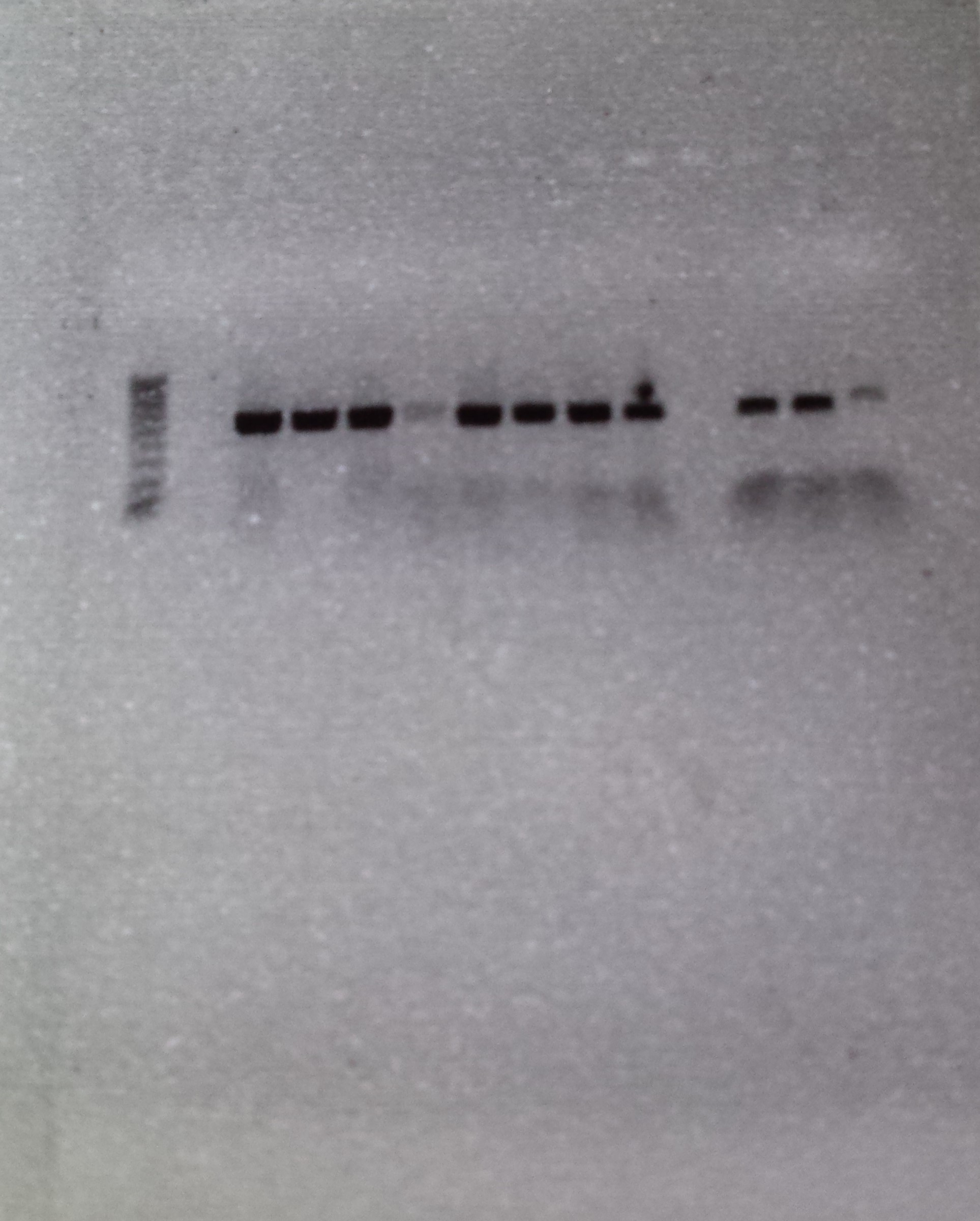

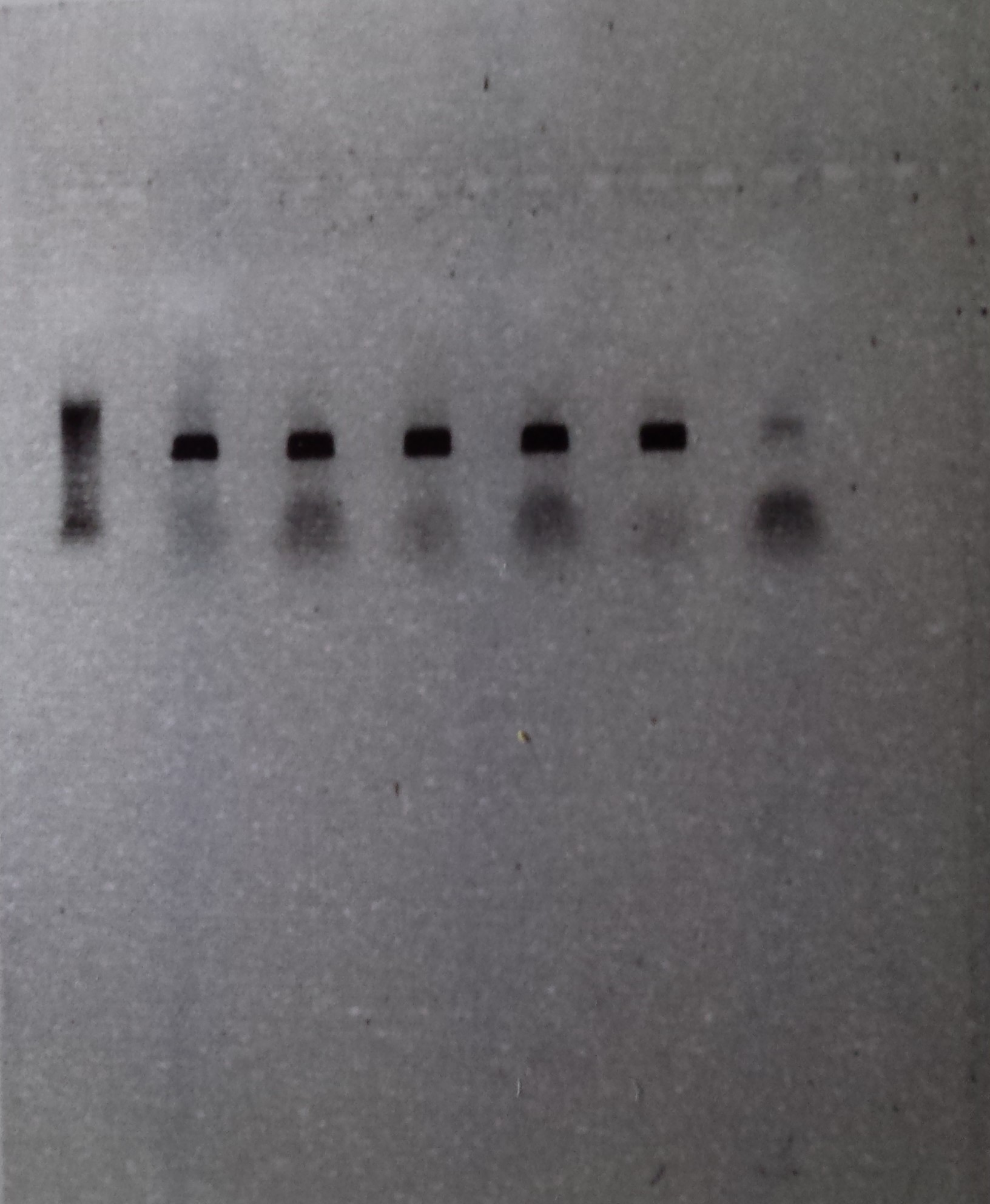

Once the PCR machine has run its course, the test tubes are removed, hopefully containing many copies of the gene you want to sample. To test whether the entire process has worked, the amplified DNA samples from the PCR step are inserted into wells in an electrophoresis gel. When an electric current is run through the gel, the negatively charged DNA molecules are pulled through the gel by the positive charge created on the other end of the gel. The gel is porous so the smaller fragments move further through the gel than the bigger fragments, and thus a ladder of different-sized DNA molecules is created. Once 30 minutes have elapsed, the gel is removed from the gel tank and is placed in a machine that takes a picture of the gel.

If you have have been accurate and everything has worked as it was supposed to, you should get a picture with a row of dark black DNA bands across your gel. A dark band is created if the desired gene has been amplified correctly in a particular sample and a row of bands is created if multiple samples have worked together.

Figure 4: Row 1- Ladder of differently sized DNA fragments, against which you can compare your samples. Row 2-6- Bands created by the presence of large quantities of the 16s gene, which bunch together because they share the same DNA fragment size. Row 7- Blank, contains no DNA and is inserted as control to ensure that no contamination is present. This sample had a little contamination as you can see above

The above picture shows the result of 5 successful extractions, with each dark band representing the amplified DNA of a individual spotted skaapsteker. Seen as though this picture was taken a few months ago, the DNA has already been sent to Macrogen, along with 10 other samples, for sequencing. I am happy to say that from this batch, 9 out of the 15 DNA samples produced viable sequences, and following the successful acquisition of more sequences from more localities, these samples will be used to determine whether there is a need for taxonomic reevaluation in the spotted skaapstekers.

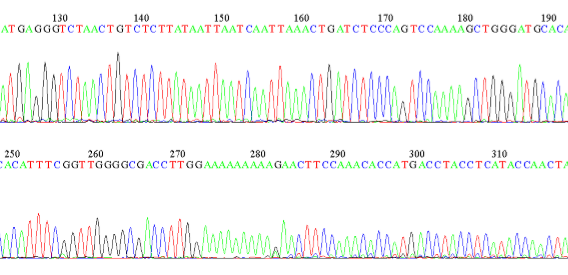

Figure 5: Example of a sequence showing the bases along a section of an DNA strand in a spotted skaapsteker.

In 2015, I completed my first project as a Zoology student, and I am proud to say it is currently being peer reviewed for inclusion in the Biocontrol Science and Technology journal. It has been submitted as a short communication (a shortened version of a scientific paper). In addition to being submitted for peer review, it was also presented at a Scientific Conference earlier in 2016 by my supervisor, Dr Philip Weyl. The abstract for the conference presentation can be found at the link below but for ease of reference, I have included the full abstract below, so that you can read more about the project. I have also attached my final presentation at the end with a collection of pictures that can explain even more clearly exactly how I explored the elements within the study and what my results were.

Abstract from invasives.org.za:

The effects of water stress on the efficacy of the biological control programme against Myriophyllum aquaticum

Chad Keates, Philip S.R. Weyl, Martin P. Hill

Biological Control Research Group, Department of Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown

There are several factors that may influence the efficacy of a biological control programme but one that has received relatively little attention is water stress. The biological control programme against Myriophyllum aquaticum has been extremely successful under most conditions in South Africa. However, field observations suggest that the beetle Lysathia sp. is not as effective in seasonal ponds – where at certain times of the year the weed grows on the banks under water stressed conditions. This study aimed to determine the effect of water stress on the ability of Lysathia sp. to feed and oviposit.

The study was conducted in two phases under controlled conditions. The first phase tested whether the females chose to oviposit on water stressed plants and, secondly, whether the eggs and larvae would survive under water stressed conditions. The study showed that when given the opportunity, the females chose to oviposit on healthy plants as opposed to water-stressed ones (Z(1,20)= 2.803,P= 0.0054). However, the larvae of Lysathia sp. were able to feed and develop with no significant differences on both water stressed and non-stressed parrots feather (U(1,10)= 11.0 P= 0.834).

This study suggests that Lysathia sp. is capable of developing on water stressed plants but, when given the choice, adult females would rather disperse to another locality where plants are under potentially better conditions. This suggests that biological control on water bodies that have a tendency to dry seasonally may not be as effective as permanent water bodies.

Link to abstract:

Abstract in the 43rd Annual Research Symposium on the management of Biological Invasions

Powerpoint presentation of project:

Keates Zoology Project presentation semester final final

Unlike last year which saw me producing one project in pursuit of my zoological degree, this year is quite different. This year I am expected to produce two projects. Both fall within the field of herpetology but that’s about all they have in common. My other project which ventures to unravel the secrets of spotted skaapsteker distribution patterns’ is a genetics project. The project that I will explain now is a biological control project.

Unlike last year however, this project doesn’t detail the effect of water-stressed aquatic weeds on insects but rather the effect of painted reed frogs on water hyacinth biocontrol agents. Biological invasions are common place in the world, with many invasive species being introduced into new ecosystems both intentionally and unintentionally. Some are very bad for the local ecosystem and its animal and plant inhabitants, but some invasions confer no negative effect on the environments.

Water hyacinth and it’s spread through South African aquatic ecosystems is neither good nor neutral, one could venture to call it a parasite on the nation’s natural water resources. Water hyacinth is a menace because unlike indigenous water weeds, it has no natural enemies and thus it grows out of control, thereby chocking species of indigenous plant life, which struggle to keep up.

Water hyacinth is a very real threat to South Africa’s water bodies, and although there are many ways of combating it’s spread, very few are successful. Herbicidal control kills the water hyacinth but kills indigenous plants and animals too. Mechanical removal is painstaking and ineffective because the smallest piece of plant can re-establish somewhere else, if it is not killed completely.

These failures led scientists to look at water hyacinths’ natural enemies for answers. Biological control involves bringing in enemies from the plants natural environment and introducing the foreign enemies in our ecosystems, granted they do not pose any threat to local fauna or flora. In doing this the plant is exposed to an organism that can recognise, eat and thereby deplete its density.

In water hyacinths case, this natural enemy is not one but many, but the ones we are going to focus on is a plant hopper (M. scutellaris) and and a mirid (E. catarinensis) species from Brazil. Both biocontrol agents have been relatively successful in controlling water hyacinth. Both biocontrol agents are currently being reared at the Waainek Mass Rearing Centre at Rhodes University. The problem is, recently, painted Reed Frogs (Hyperolius marmoratus verrucosus) have been found in the mass rearing pools, the same pools that rear the insects.

The project thus aims to determine whether the frog predates upon the two insects. If the frog does in fact incorporate either of the two insects into its diet, it could affect the Waainek Mass Rearing Centres’ ability to rear and distribute the insect, and if they cannot rear the insect in high enough quantities, then water hyacinth will continue to take over South African waterways without restriction from the biocontrol agents.

Red Hartebeest, Blesbok, Plains Zebra and a single Black Wildebeest at Lalibela Game Reserve

Yesterday I accompanied Gareth Nuttall_Smith on a trip to a local game reserve, to setup his Masters project. The project which involves both vegetation transects and camera traps, aims to determine the effect of elephant presence on thickets throughout the Eastern Cape.

We set off for Lalibela Game Reserve, one of the 11 reserves, on the Monday afternoon and managed to set up all three camera traps that same day. Whilst it is relatively simple to setup, it’s the process beforehand that requires the most attention, because before we even got to the reserve, Gareth had already contacted management, setup and attended a meeting, developed maps and plotted random points for camera traps.

Gareth Nuttall-Smith setting up a camera trap

By the time I had got in the car, most of the work had been done. All I had to do was accompany him on his drive to the three localities and watch him zip tie three motion-sensitive camera traps to three sturdy trees overlooking animal pathways. Once secured the traps are left alone for months on end in hope that they will capture the activities of animals in their day-day to lives. At the end of the sampling period, the photos will be pooled together across all the reserves, and Gareth will determine statistically if what the cameras have captured, means anything.

Once camera-trapping was complete, Gareth and I drove to Amakhala Game Reserve to spend the night so that we could complete the whole procedure, again, the next day. Once we arrived, we unpacked, setup a fire and went looking for reptiles. All I found was a cape skink but I lost it as soon as I found it. We ate supper, retired to the old manager’s house and we went to bed. I struggled to sleep for a while because I was creeped out be the ancient interior which looked more like a scene from a horror film than a home.

The next morning, we were back in the car, accompanied by a game ranger, in search of one of Gareth’s vegetation transect sites. We arrived, got out the vehicle and started walking. I was last in a line of three people, who were now, blazing a trail through the bush, until, all of a sudden, the party came to a crashing halt. This was because, in front of us stood, an entire herd of rhino. We backed away slightly as the large male pushed his head through the thicket to exam us more clearly. We were about 15m away, but soon increased that number when we decided to head back to the car in search of another site whilst the rhinos grazed.

Once in the car, Gareth selected another section of the park to sample, and we were off. Unlike the prior site, this site was free of rhinos, and luckily, lions too. Vegetation transects, unlike camera trapping, are not so easy and involve sampling the vegetation type and structure every 10m along a 280m transect. It is labour intensive and must be completed at least three times at each of the eleven parks. To put it simply, Gareth has a lot of work to do.

About an hour and a half after starting, we finished and whilst acacias did not arouse much suspense, the warthog that nearly mauled our game ranger, did. On our way out the thicket, our party once again happened upon a rather large warthog and unlike the rhino, the warthog ran at us before deciding to book out in the opposite direction. Whilst a warthog lacks the fear factor of a lion, the tusks of a startled warthog are sure to create a rather large gnash in anyone who finds themselves between the animal and safety.

In the end, we survived. The trip was also at its end because the rhinos that we had happened upon at the last site, had not left, so it was unsafe to return to complete the sampling. In the end it was a great experience for both Gareth and I because whilst we did not finish what we set out to do, we saw a rhino face-face and lived to tell the tale.

Gareth’s car at Lalibela Game Reserve

Recently I went to Hogsback. For those who do not know, it is a quaint little town in the middle of the Eastern Cape with little to no influence from the outside world. What this town lacks in modernity, it makes up for in biodiversity. Hogsback is home to the Cape Parrot Project and the critically endangered Amathole toad (Vandijkophrynus amatolicus).

Hogsback is lucky enough to call this species home because of its position on the Amathole mountains where biodiversity and endemism is high. Other species that can be found on the Amathole mountain range include the Hogsback chirping frog (Anhydrophryne rattrayi) and the Amatola flat gecko (Afroedura amatolica) which recently, my colleagues and I found nestled under a rock on a steep recently fire-stricken hill.

This same hill was also home to one cape skink (Trachylepis capensis) and a rather bad-tempered red-lipped herald (Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia). Earlier that day we were lucky enough to find two cape geckos, five clicking stream frogs and three short-legged seps (Tetradactylus seps) in the rubble of a dilapidated house. The haul was greatest in the afternoon, and this is a testament to the temperature which rose with the sun that very day. When we arrived at Hogsback at around 9:30 in the morning all we were greeted by was chattering teeth, quivering knees and ice -stricken cape girdled lizards (Cordylus cordylus) that lacked like the motivation to run away, even when their homes were seamlessly removed from above them.

As you can gather, our first finds were several semi-frozen Cape girdled lizards which were nestled between ice-cold rocks. Whilst they were a ‘breeze’ to photograph because of their inability to move, you couldn’t help but feel sorry for them and their lack of insulation. Whilst the day was intended as a snow day, the lack of snow made it just a day. In terms of herping however, it was a massive success with many firsts for me and the people who accompanied me on my exploits in the mystical mountains, which are thought to be the motivation for J.R.R Tolkien and his world-renowned book series, ‘The Lord of the Rings.’

Regardless of the fact that I saw neither orcs nor any Amathole toads, I am happy with what I saw and what I learnt because after all its not everyday that you see a seps, nevermind three.

Trip attended by: Chad Keates, Luke Kemp and Matthew Clarke

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Midlands, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa

from Luchazes, Angola

from Luchazes, Angola

from Luchazes, Angola

from Pafuri, Limpopo, South Africa

from Augrabies, Northern Cape, South Africa

from Augrabies, Northern Cape, South Africa

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Grahamstown, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Ndumo, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa

from Ndumo, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa

from Graaff Reinet, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from Graaff Reinet, Eastern Cape, South Africa

In an attempt to revive a bygone era of mystery and exploration, Luke and I ventured into the unknown in search of the elusive yet locally abundant berg adder Bitis atropos in Barberton (Mpumulanga). Barberton, a hop, a skip and a jump away from civilisation, is one of a few locations famous for berg adders. The trip began on the 13th of July 2016 and was marked by many a sighting. Whilst the trip was intended for the discovery and documentation of the berg adder, no opportunity was missed to discover the other ectotherms that inhabit the similar rocky habitat.

All sightings were photographed and uploaded onto the ADU (Animal Demography Unit, http://www.adu.uct.ac.za).The ADU is an online database that utilizes the sightings made by citizen scientists to create distribution maps of the organisms of South Africa. Luke and I, budding zoologists and aspiring herpetologists, utilized the ADU whenever we found a new reptile to ensure that our effort in the field translated into knowledge that could be used by others and hopefully us one day to conserve the animals we held most dear to our hearts. We were experienced going into the trip but we were well aware of the season. Winter is cold as I’m sure you know, and this makes ‘herping’ that much harder because of the cold-blooded nature of the animals we hope to find. Reptiles become more scarce in winter and although unfavourable for those who wish to find them, finds that are made are much more special during this season.

Berg adders are diurnal dwarf adders that are relatively common yet hard to find. There scarcity from human eyes is a testament to their cryptic colouration, their small size and their preferred habitat which can be as high as 3000m above sea level. When found however, the snake will bite readily, injecting a nasty venom which is potentially fatal to humans.

Our first day, which began on the jam-packed roads of the N1, ended with a rather favourable tally. We found three black-headed centipede eaters, one common crag lizard, one spotted day gecko, several snake-eyed skinks, several thread snakes, one Bibrons blind snake and one cross-marked whip snake. Whilst our first day didn’t produce the berg adder we so sorely desired, it was rather productive and a benefit to our skills, which improved with every rock flipped and reptile identified.

Whilst the life of an amateur herpetologist may seem glamorous to those that look upon their findings, many if not most of the rocks that one flips in search of reptiles turn up no results. Herpetology requires patience and persistence and a lot of luck and if you have all three you still might struggle to find the most elusive species.

“What is a biologist without a sense of adventure, the urge to see it, find it and document it. Many biologists these days are gene jockeys, thriving in the sterile comfort of the lab. Not to say there is anything wrong with this, in fact genetics plays a large role in modern science and understanding species. Yet gone are the days of Wallace and Darwin style adventures out into the remote areas observing organisms in undisturbed habitats.” Luke Kemp

Before departing on our trip to the border of Swaziland, Luke did some research on the berg adder and found that they are most common on the highest mountains. The second day of our journey thus began with a trip to the highest mountain in the area. Once we found the area that we believed to be the highest we set off up the mountain flipping every movable rock in our path. The journey upwards was marked with seven montane dwarf burrowing skinks, two black headed centipede eaters, several thread snakes and one Transvaal girdled lizard. Once we hit the summit of the mountain we were once again found wanting, as the one species we had been searching for still eluded us.

We decided that the mountain just in front of us yielded our best chances of finding the berg adder as the one we were on was deemed challenging by the local herpetologist, which Luke was now frantically texting. We thus set off, with my spirits dampened and Luke photographing a baboon spider for a South African arachnologist, I haphazardly removed a rock, and upon returning it to its rightful place, saw something in the long grass beside me. My initial thought was ‘girdled lizard’ but upon closer inspection, and to my surprise, the word ‘berg adder’ sprang to mind. I yelled and Luke responded. After some shuffling and a bit of squealing we removed the rock that was now obstructing the animals hide and found a beautiful, yet aggressive, female berg adder.

“Zoology, the profession where it is acceptable for one to play around in the veld looking for gho-gho’s all day. For what is better than being a big kid in a big world with something new to find under every rock?” Chad Keates

Pictures were taken and coordinates were marked. We were over-joyed with our find but our luck was still not up. Ten metres away from the place where we found our female, we found a male, nestled underneath a small pile of rocks. The trip was a great success, our goal was achieved and the night was upon us. On our way down we were lucky enough to find a parting present after a great day of ‘herping’: a large Wahlberg’s velvet gecko nestled between two slabs of rock.

We left Barberton the next morning but before doing so we decided to do one more hike up the mountain closest to us. We found one Van Son’s gecko, two sandveld lizards and three variable skinks. The trip was now officially done but we were happy because we knew that this was just the beginning; the beginning of a career flipping rocks and finding critters, the beginning of a career in the middle of the wilderness, a career in zoology. We would be back one day, hopefully with several more Rhodes degrees behind our name.

Special thanks goes to Luke Kemp for his input in the synthesis of this article, which featured in the Rhodes University Department Newsletter

I have loved snakes for as long I can remember. They fascinate and inspire me to read more and more. They very well may be the thing I choose to base my life’s work on one day, and it’s this love that has steered me towards my latest Zoological endeavour: the study of spotted skaapstekers and their distribution In South Africa

Unlike my first project which saw me growing buckets upon buckets of invasive water weeds, this project has me in an air-conditioned lab with finely-tuned scientific instruments – a hop, a skip and a mile away from my previous greenhouse and spade. It may not be as glamorous as birthing a T-rex but it has its perks. Firstly, it doesn’t pay. Secondly, it makes me feel stupid and thirdly, it makes me feel more stupid than the laboratory’s pet fish that eats its own semen. Granted, these are not perks but the semen eating Siamese fighting fish is weirdly frightening and fascinating all at the same time. (P.S. I don’t know if the fish’s diet is completely factual but I have it from reliable sources that it is).

Regardless of the fish and its diet, I believe this project is both challenging and rewarding at the same time because it promises new knowledge and new skills that are tantamount to the arsenal of any aspiring herpetologist.

Thus far I have completed the DNA preparation for most of the DNA samples from the Bayworld museum in Port Elizabeth. The preparation which involves clipping body tissue, extracting, amplifying and running DNA is a rather painstaking and unpredictable process which leaves even the most robust knees shaking from side to side. The end product, a small picture with an array of black and white lines can make or break your day and luckily for me, my day was made the first time I delved into the world of genetics.

My DNA samples were good and for this reason they were packaged and sent to South Korea only weeks ago for further preparation. The product of the preparation carried out in South Korea will be inputted into a rather sophisticated programme to determine whether the samples ascertained from the museum prove or disprove the existence of multiple subspecies of spotted skaapsteker in South Africa.

The project is still in its early stages because I have only done approximately a third of the necessary DNA preparations for the project. The next step which was begun only days ago will involve me preparing spotted skaapsteker DNA samples from SANBI (South African National Biodiversity Institute) in Cape Town. Once prepared, the large batch of samples will be sent to South Korea and following that will be analysed in conjunction with the samples from the Bayworld to determine whether spotted skaapstekers are perhaps more than just one species.

Although I am only at the beginning of this sure-to-be stressful endeavour, I am excited to see what the future holds and whether the spotted skaapstekers warrant taxonomic reevaluation.

In the animal kingdom, the ability to reproduce is one of the most critical abilities in an animal’s arsenal because it ensures the survival of the species. There are however three different types of reproduction namely viviparous, ovoviviparous and oviparous reproduction. Viviparity is the ability to produce live young, oviparity is the ability to produce eggs that hatch outside of the uterus and ovoviviparous reproduction is the retention of the egg within the uterus until hatching.

Viviparity is the most recently evolved method of reproduction and has evolved over 160 times in animals. Viviparity is thus present in bony fish, amphibians and most mammals with at least 20% of the snake and lizard species displaying viviparity. What is so interesting about viviparity is that is not present in any birds yet it is present in both lizards and snakes which represent an older order of animals. Birds date back to the Jurassic and there are approximately 9000 species of them which exhibit incredible morphological and ecological diversity, yet not one of them has the ability to produce live young.

The only other class among the vertebrates that cannot produce live young is the class Agnatha which represent the lampreys and hagfish. They lack the prerequisites for viviparous reproduction which include internal fertilization and a chamber rich in blood vessels for incubating the developing egg. Birds however have both of these physical attributes.

Why don’t birds produce live young?

Many hypothesis exist to explain the lack of viviparity in birds but the two most studied include the flight hypothesis and the cledoic egg hypothesis. It is hypothesised that flight is a reason viviparity is absent from the bird kingdom because internal development of an embryo would incur additional weight on the bird and negatively affect the ability of the bird to fly. The hypothesis is however not fool-proof because flightless birds (ratites) such as ostriches still produce eggs even though they lack the ability to fly. Bats are another example because although they are mammals and subsequently produce live young via viviparity, they are highly accomplished fliers.

Birds have cledoic eggs which are highly calcified and thick, they allow the movement of gases but are poor at allowing the movement of water and nitrogenous waste through the walls of their shell. Bird’s eggs resemble crocodile and turtle eggs very closely and of the 250 species of turtle and 21 species of crocodile neither of them have evolved viviparity, making the cledoic egg a possible reason for the lack of viviparity in animals. Embryos have a high metabolic requirement and due to the specialised shell of the bird, don’t grow well in the low oxygen and high carbon dioxide environment of the uterus.

Another hypothesis is that the internal temperatures of birds are unsuitable for the production of live young. The resting temperature of birds is approximately 41 degrees whilst the optimal temperature for egg incubation lies between 34 and 38 degrees. In chickens, eggs have a higher chance of mortality if they are retained by the mother for too long due to an excess of heat and carbon dioxide.

Viviparity is a reproductive strategy and would only evolve in birds if the benefits of having it outweighed the costs. In simple terms maybe viviparity never evolved in birds because oviparity was already a successful form of reproduction.

Birds have adapted a suite of reproductive strategies that work hand in hand with oviparity. These include the production of multiple offspring, complex parental care and incubation. Developing embryos are protected from disease and environmental factors by the albumen, egg shell and the accompanying membranes. Parents provide protection and warmth via thermoregulation whilst egg camouflage and nests protect the eggs from predators. The introduction of viviparity could very well decrease the fitness of birds by reducing the amount of offspring they can produce, increasing the chance of death in the mother and reducing the amount of male investment in chick rearing.

The special adaptations associated with egg laying in birds probably evolved early in the history of the class and certainly before the period in which birds started diversifying into the many species we have today. Although it is unknown why birds reproduce in the way they do it is common knowledge in the scientific community that they are a highly successful class that reproduce highly effectively regardless of the fact that they still lay eggs.

How does viviparity occur in snakes and lizards?

If not a single bird is able to produce live young, how it that snakes and lizards are able to when all of their ancestors previously produced eggs.

Firstly, birds are very different from the oviparous vertebrate ancestors that eventually made the leap to viviparity. Secondly, not all reptiles are able to reproduce live young. Neither the dinosaurs of the Jurassic period nor the crocodiles or turtles of today can produce live young.

What links all these animals is the structure of the egg: the eggs are thick and heavily calcified, making it harder for certain gases to pass through their membranes. In the closed off environment of the uterus, gas movement becomes an even bigger problem. Squamate (snakes and lizards) shells are markedly thinner and less rigid making this less of a problem.

In the squamates it is believed that exposure to cold environments is one of the deciding factors in their movement towards producing live young. In a cold environment the egg of the mother would experience that cold because of its presence in the nest. These cold conditions could slow or even cause death in the developing embryo. If the egg is retained within the mother its chances of survival are markedly improved because it can acquire the optimal incubating temperature from within the mother because she can attain a high body temperature through her interaction with the environment.

Other factors that influence the evolution of viviparity in squamates include predation, flooding, dehydration, ultraviolet attack, microbial attacks and moisture extremes. If a mother is burdened with an embryo she is less able to move and feed which can be a limiting factor, but when it comes to reptiles such as snakes and lizards, they tend to huddle around their eggs once laid to protect them so retaining the embryo won’t make much difference to the female.

In terms of predation, if the egg is retained within the female it can’t be eaten unless the mother herself is eaten. Finally moisture extremes on the ground can cause disease so if the egg is retained, it is protected from extremes in the environment.

Conclusion

Much like birds, the reproductive capability of live birthing will only evolve in squamates if the benefits outweigh the costs. In order to become fully viviparous, evolution must favour the intermediary stages because evolution is gradual. What this means is that an animal isn’t instantly viviparous but rather becomes viviparous over time with changes such as the lengthening of the time the egg is retained within the female and the development of a placenta. In certain squamates it is clear that viviparity is beneficial because it exists in the animal and thus the lack of viviparity in birds is a sign that birds don’t gain any benefit from viviparity because no viviparous birds exist.

from Haenertsburg, Limpopo, South Africa

from Haenertsburg, Limpopo, South Africa

from Haenertsburg, Limpopo, South Africa

from St Francis, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from St Francis, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from St Francis, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from St Francis, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from St Francis, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from St Francis, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from St Francis, Eastern Cape, South Africa

from George, Western Cape, South Africa

from George, Western Cape, South Africa

from George, Western Cape, South Africa

from George, Western Cape, South Africa

Chad Keates

Chad Keates